Team Name: Cornell Tech 2021 Product Studio Team 3

Tingyue Wang: Communication Design BFA, Parsons

Adhiraj Singh: Tech MBA Program, Cornell Tech

Ashley Shen: Operations Research and Information Engineering ME, Cornell Tech

Dorothee Grant: Computer Science ME, Cornell Tech

Jiejun Tian: Electrical and Computer Engineering ME, Cornell Tech

Project Duration: 4 Months, September - December, 2021

Related Course/Activity: Cornell Tech Product Studio 2021 (Our group matches with Accenture)

1 . Product Narrative

The pandemic has disrupted work-life balance. Pause.io is a SaaS platform that aims to mitigate mental health concerns among employees by affording greater flexibility in work styles. It achieves this by mandating work breaks for employees with personalized activity recommendations.

2. How we arrived at this product as a response to our How Might We

Our initial HMW is open-ended, we knew we had to narrow it down in order to solve a tangible problem.

From early on in our user and industry research, we found that mental health was a very common concern among professional employees. We found this to be repeatedly mentioned across different industries and from fully remote, hybrid, and in person employees, therefore we thought narrowing our focus to this target audience would yield the most successful results.

From this point on we iterated over several ideas, after iterative feedback and de-risking we found this idea to be the most do-able and desired by our target audience.

3. Learnings from the experiments

Implementation will be a problem. As is, there is no incentive for employees to voluntarily use this software, as it hinders them compared to their co-workers (especially in more competitive domains such as Investment Banking).

Notifications can be ignored very easily, especially over-time. While the results were overall positive, it only lasted a day, in order to de-risk this more, we would need to increase the length of the test overall.

Limited working hours does not seem to impact the ability to finish a product on time.

Moderate levels of personalization in the messages would yield the most positive actionable responses overall and should be a part of the implementation configuration. However, further research is needed to figure out the most effective wordings for each recommendation.

Highly personalized and detailed recommendations yield the least positive actionable responses. Thus, moving forward, it’s important to set a clear line between high levels of personalization and moderate levels of personalization.

4. Experiment Design

Experiment 1: Pilot with manual reminders via text

Participants

We recruited 9 employees in the professional industries. While we would ideally like to recruit these individuals randomly, we ended up recruiting through word-of-mouth, which led to a key finding of this experiment we will discuss later.

Experiment

Nine participants were broken up into three groups:

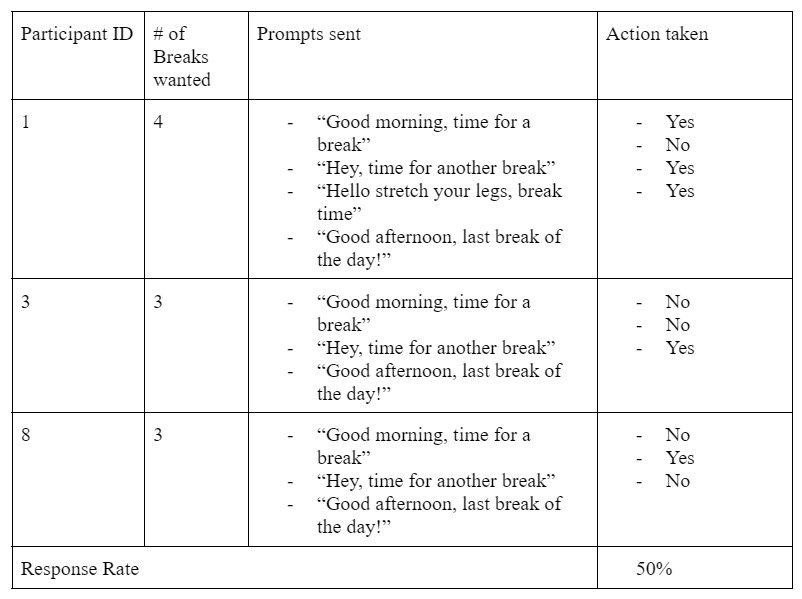

- Group 1: Received very low detail prompts

Ex: “Take a break!”

Ex: “Take a break!”

- Group 2: Received moderately detailed prompts

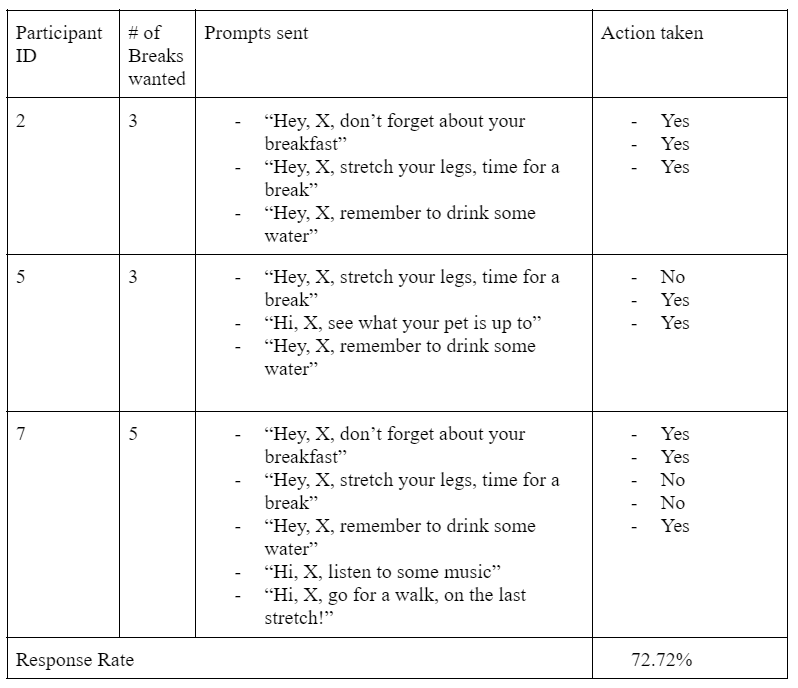

Ex: “Hi, Stephanie, it is time for some self care!”

Ex: “Hi, Stephanie, it is time for some self care!”

- Group 3: Received highly detailed prompts

Ex: “Hi, Emily, go listen to Taylor Swift (the new album is out), it is time for your break!”

Ex: “Hi, Emily, go listen to Taylor Swift (the new album is out), it is time for your break!”

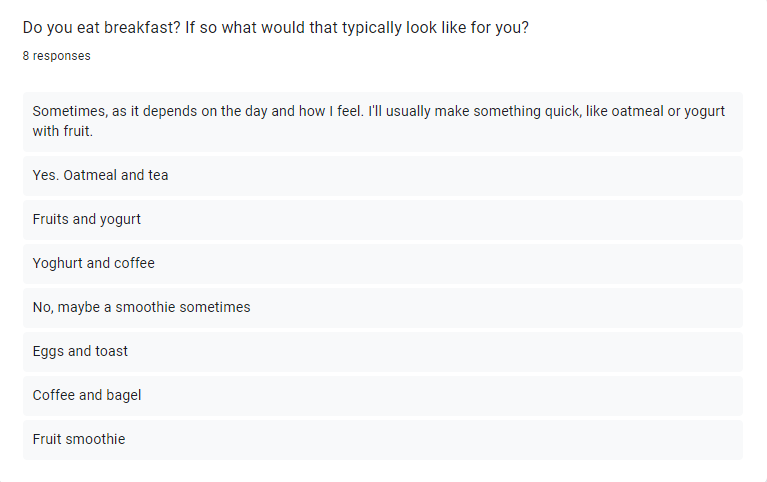

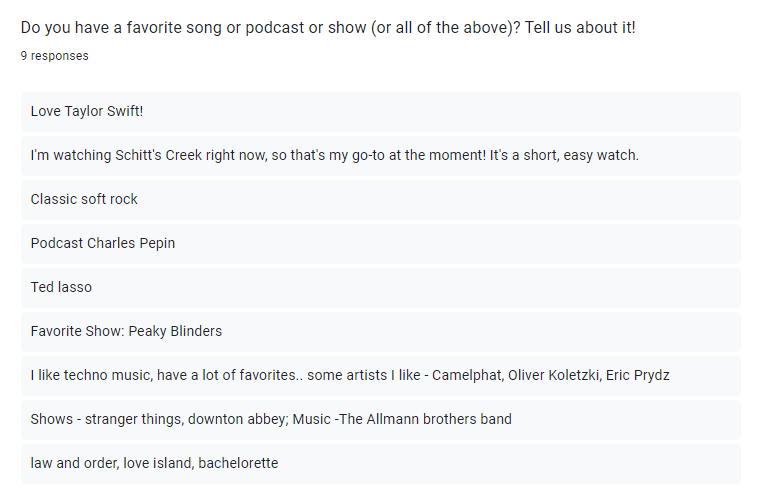

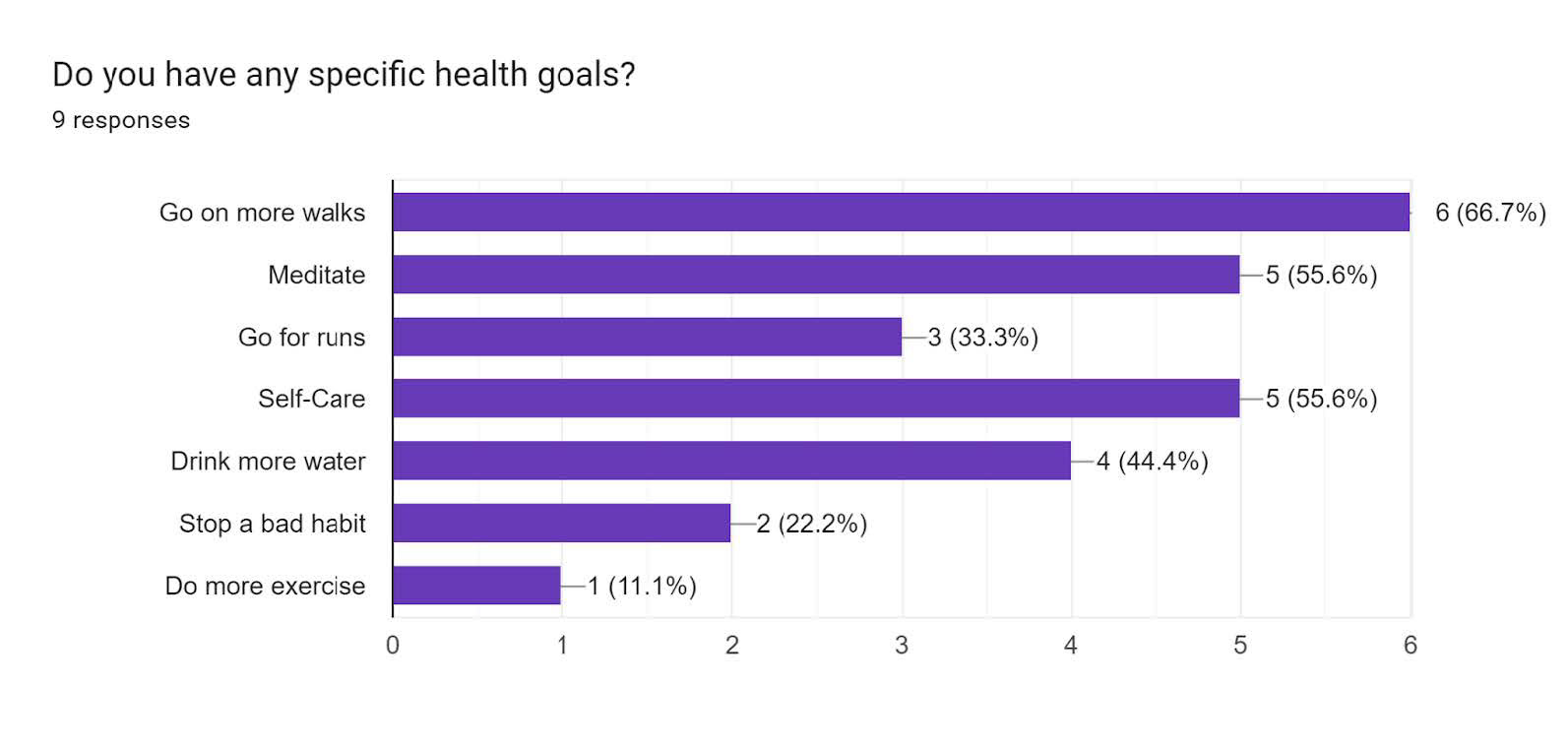

The content for the breaks was gathered from results we sent out in a survey beforehand; this would be a one-time action but can be continually updated when the user wants to adjust.

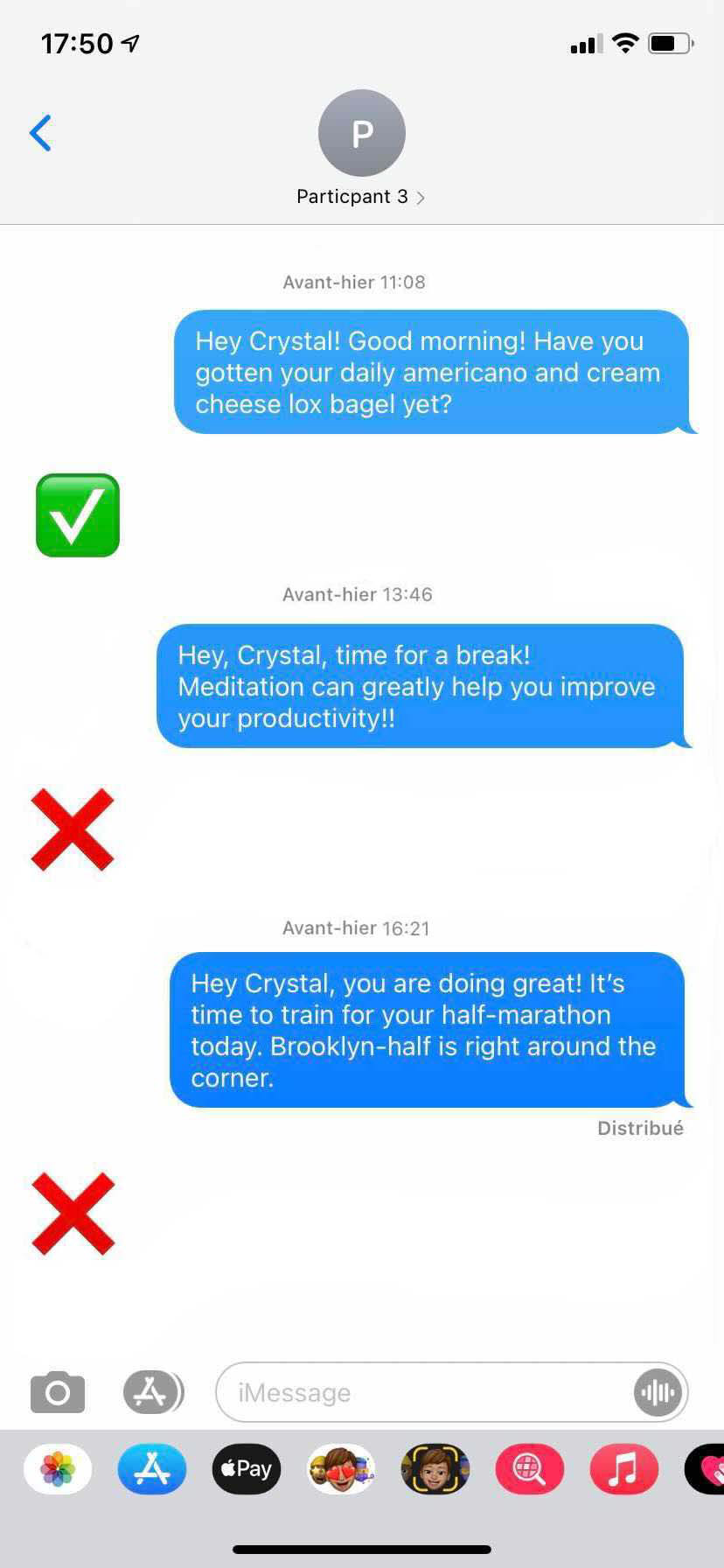

In order to determine the response rate, we use two metrics: first we use zoom to monitor employees and see how they react, second we ask the user directly to provide feedback. We do so by asking them to provide a checkmark (✅) if they took action based on our prompt, and an X (❌) if they did not. Then we compared the response rate from three separate groups and obtained the optimal level of personalization of suggestions.

For privacy reasons, our team won’t share any of the survey results and participant’s personal information with any other organizations and we will strictly keep the data anonymous.

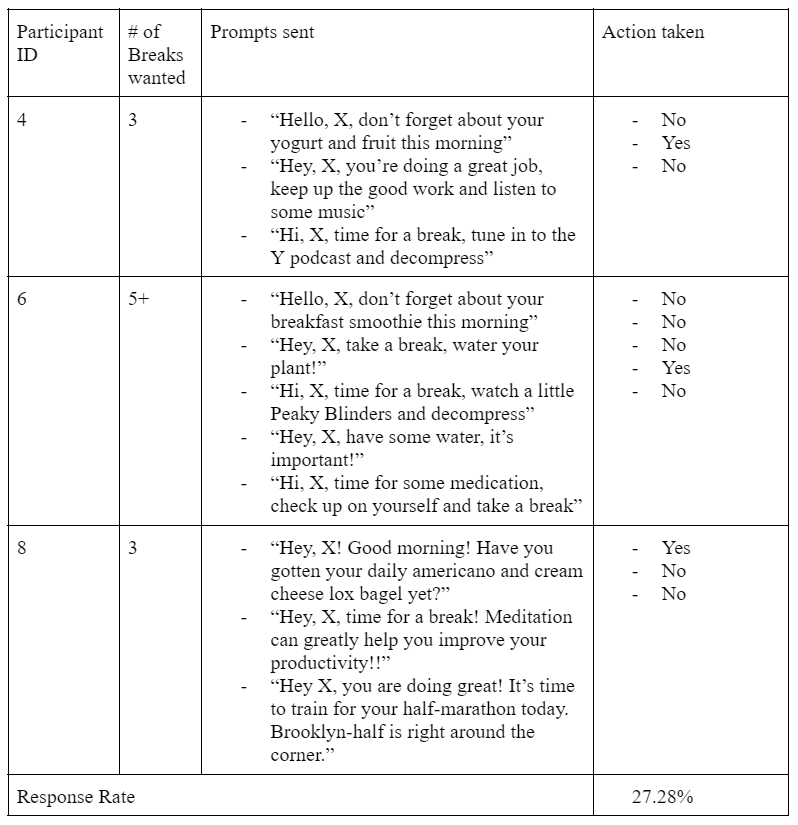

Group 1

Group 2

Group 3

Conclusion

From this experiment we learned several key features that would need to be adjusted in order to move forward. We learned that a moderate amount of details (the employee’s name and an open-ended activity) produces the highest response rate compared to less and lower amounts of details. A potential reason for this could be that too high levels of detail encourages the user to do just that activity, and if they are not in the mood or able to do it, then that message is not relevant. While very little detail did decently, we think that the open-endedness can be positive, as it appeals to all groups, but also too generic to really impact our users.

While the concern regarding levels of personalization was de-risked, we found a larger problem: friction in implementation. Our team had a lot of trouble recruiting volunteers to take part in this study, and this concern extends to how it would be received in the real world. We think this is such a big risk, that we would need to pivot and alter our product to mitigate this problem by working with specific companies, employers, and managers directly, for a top-down approach. We came to this conclusion, because the most common response to asking for volunteers in this experiment was a feeling that the employee would only be hurting themselves if they were a part of it, and since their boss wasn’t doing it, it would look bad on them. Going back to our initial prompt “how might we help employers meet the needs of their employees…,” pairing directly with the employees would aid in the implementation process as long as they are dedicated to helping restore work life balance, and improve the wellbeing of their employees.

Experiment 2: Equivalent Experiment on timeboxed work hours

Participants

To conduct this equivalent experiment, we needed to get participants that were incentivized to do the same work, whose work could be timeboxed, and that we could get unbiased results as to performance. Therefore, we invited 4 pairs of students from Human-Computer Interaction class at Cornell Tech and randomly assigned each pair into Group 1 or Group 2 for the experiment. Those 8 students had the same homework assignment due on Wednesday, December 1st. The assignment was about the heuristic evaluation of a product they designed in the class. As per the requirements of HCI, the assignment would be submitted in the form of a 2-person team.

Experiment

The 8 participants (four teams total) were separated into two groups and they both were required to complete the same HCI assignment in the same time period.

- Group 1: No daily time constraints. They could work on the assignment anytime of the day or night they preferred.

- Group 2: Had a constrained working time slot. They were required to work only between 10:00 A.M. and 6:00 P.M. everyday.

- Group 2: Had a constrained working time slot. They were required to work only between 10:00 A.M. and 6:00 P.M. everyday.

The 8 participants (four teams total) were separated into two groups and they both were required to complete the same HCI assignment in the same time period.

Our group highly respect and value our participant’s privacy and therefore we will keep the anonymity of their identity, work, and grades, and we won’t share this information with any other organizations.

Conclusion

The conclusion of the experiment is dependent on two key metrics - completion and performance. The completion metric measures task completion by both groups given the constraints and the performance metric informs us of work quality as judged by the professor.

As both groups completed the task on time, we already know that limiting work hours did not impact the completion metric for group 2. This finding suggests that there is scope to limit working hours even while prioritizing productivity. The performance of both groups is yet to be measured as we await grade awards by the professor to students of respective groups.

As each group consists of two teams of two students, the average score of the two teams will be used to measure the performance of either group. Once the assignments are graded by the professor, we will incorporate the feedback from the performance of the two groups to further tune our idea.

In case the control group fares better than the treatment group, we would need to conduct additional experiments to confirm whether performance was indeed impacted by the limiting work hours. A better performance by the treatment group would bolster our idea. However, additional larger scale experiments would likely follow so as to ensure consistency in results.

In case the control group fares better than the treatment group, we would need to conduct additional experiments to confirm whether performance was indeed impacted by the limiting work hours. A better performance by the treatment group would bolster our idea. However, additional larger scale experiments would likely follow so as to ensure consistency in results.

The magnitude of difference in scores would also be critical in assessing how the experiment’s constraints impacted the treatment group. A marginal difference would be inconclusive and would require further experimentation. However, a comprehensive difference in scores would offer greater clarity and add weights to our conclusion.

5. Demonstration of experiment

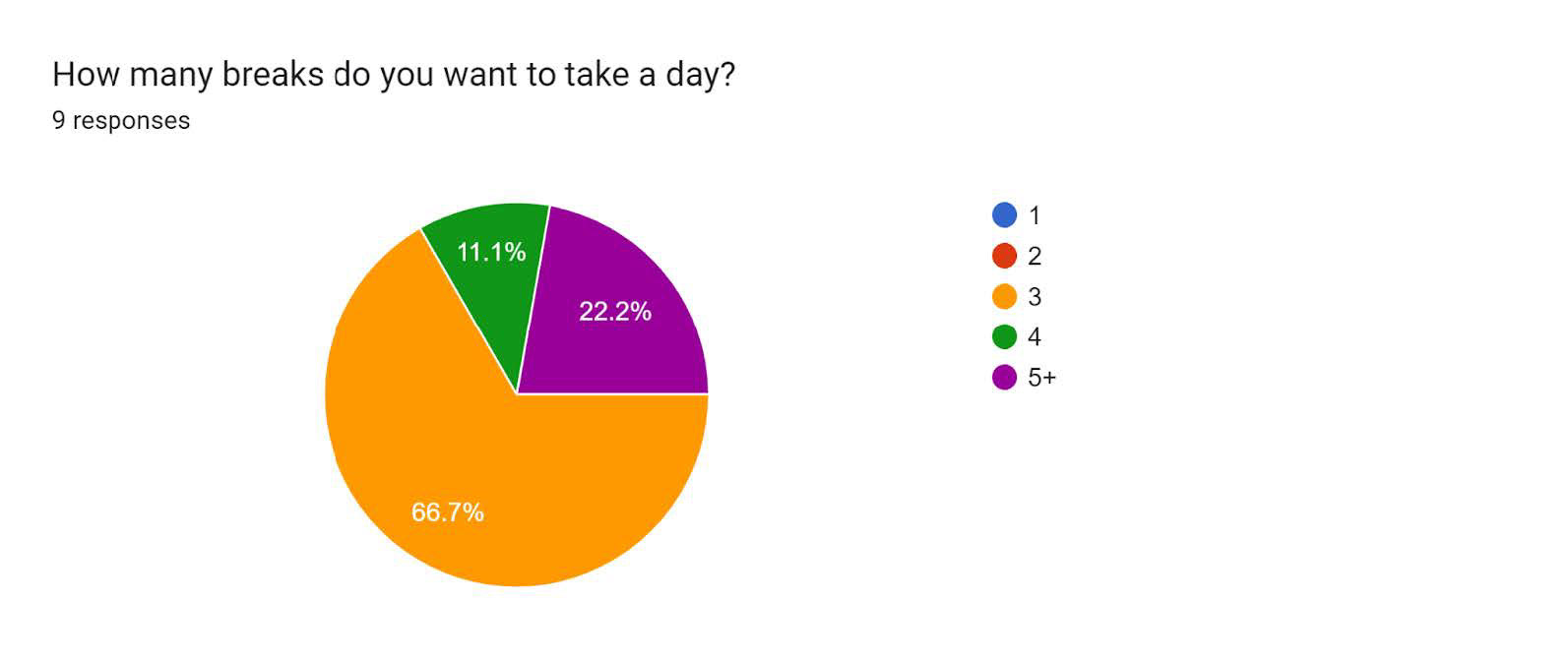

Experiment 1: Visuals from the initial survey sent out

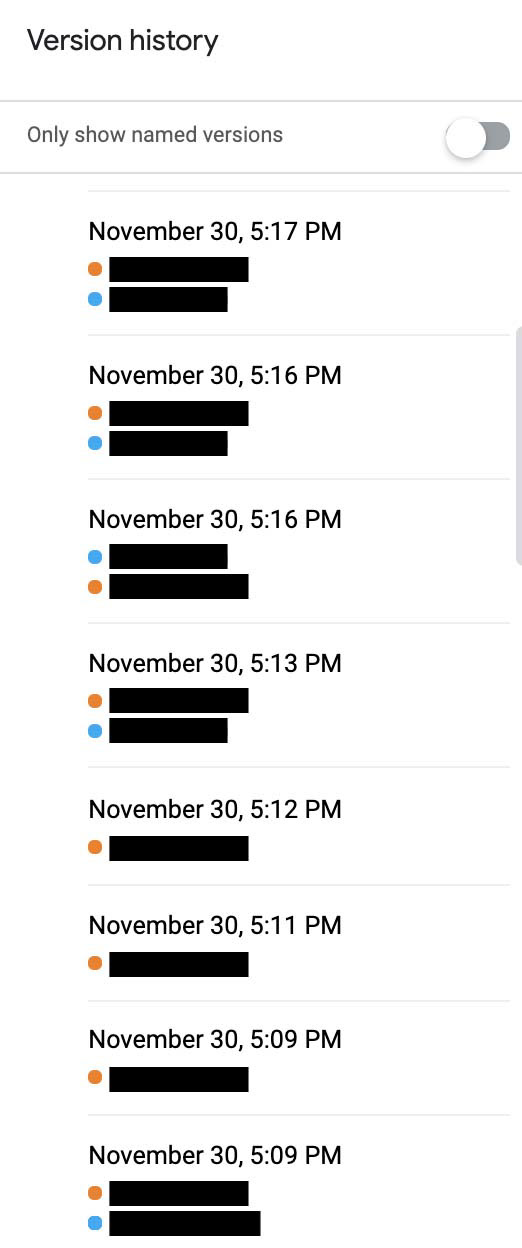

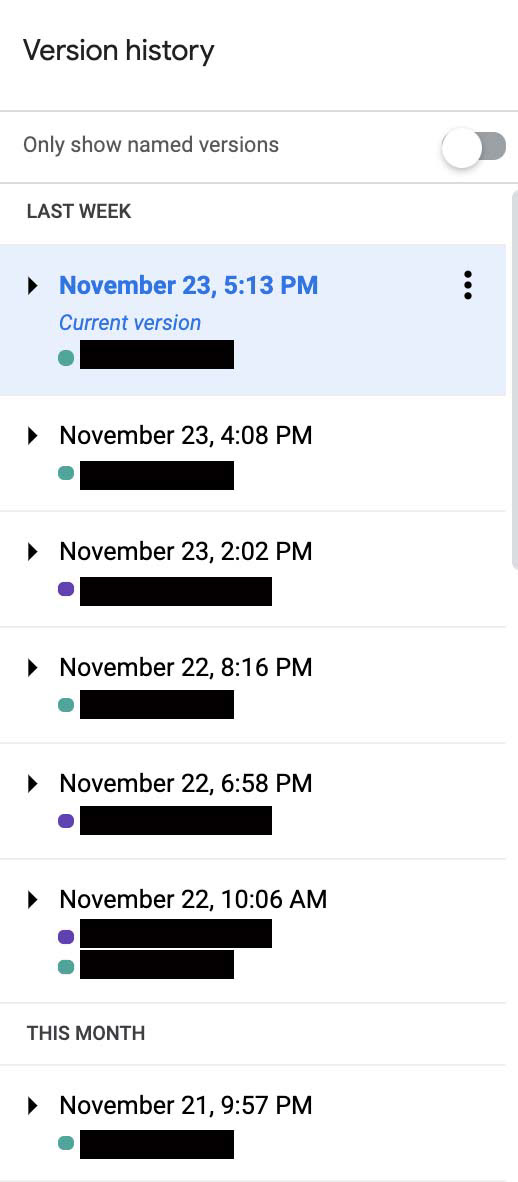

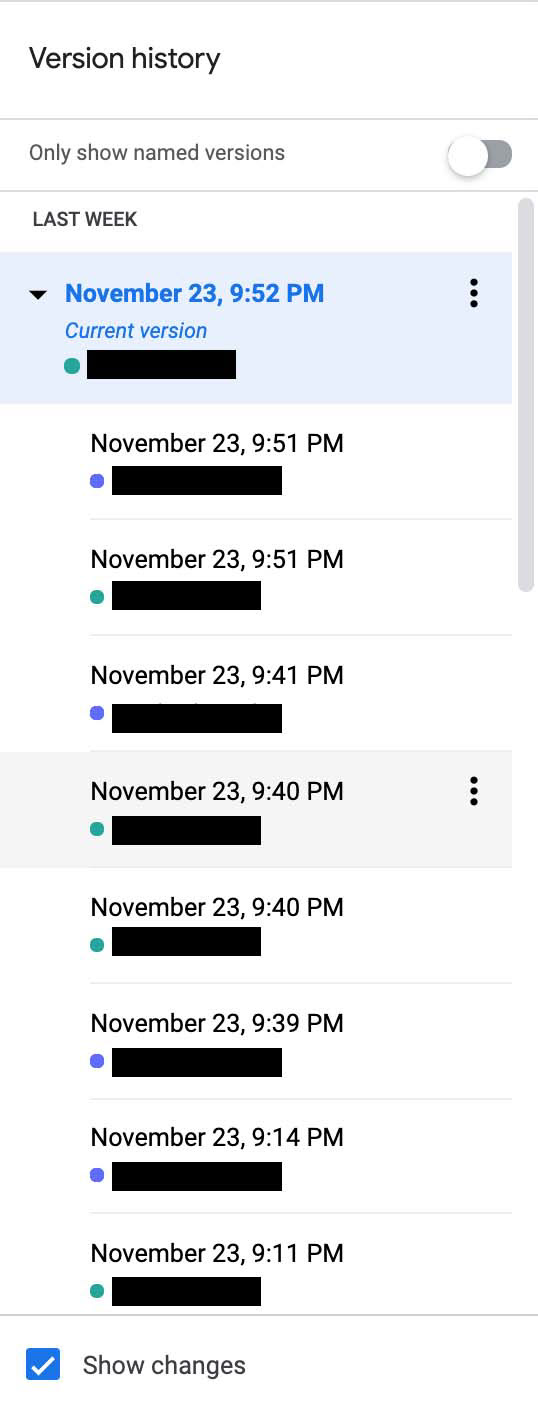

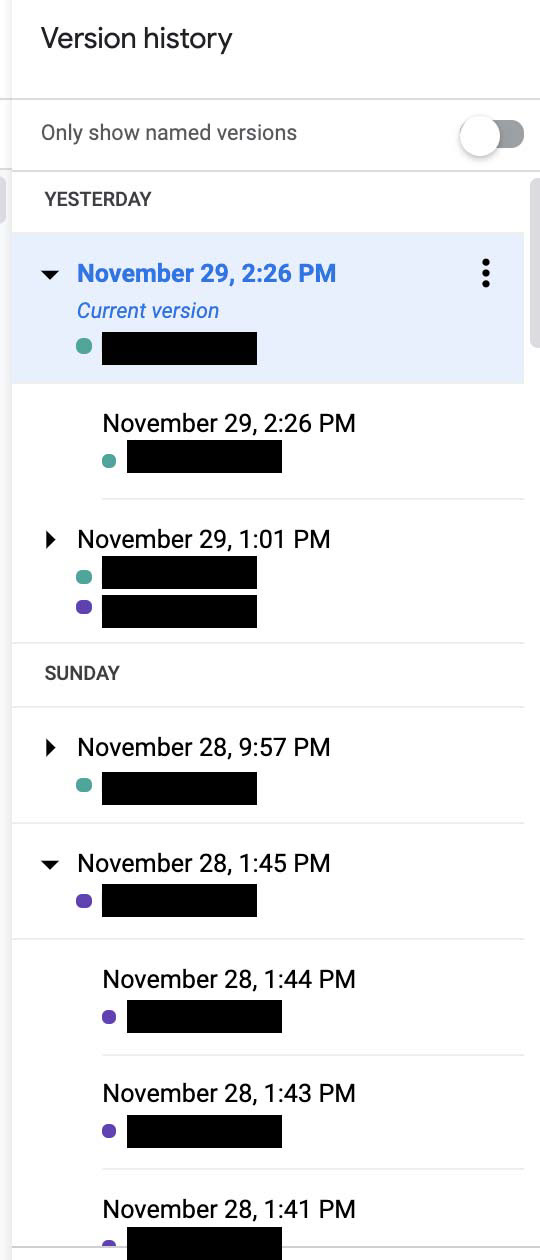

Experiment 2: Screenshot of version history of the homework assignment

Group 1-1

Group 1-2

Group 2-1

Group 2-2

6. Go-forward Plan

As is, we need to tune the configuration most likely to succeed to best put this idea into production.

There is too much friction and too little incentive for individual employees to use this product. Even in the situation where it is an add-on to an existing work software, if the product is not a team-wide tool, the employee is taking too much of a risk by using Pause. We still believe this product does promote healthier work-life balance and incentivize work-time productivity, but only at scale when an entire team/division/company is using it, and to reach many users we need to pivot.

We think that in the configuration most likely to succeed we would need to work directly with employers and integrate as a part of a working system, not as a separate entity.

A physical IoT device could increase validity and credibility, doing an experiment in this domain would be useful, and we think exploring this venture could help differentiate the product down the line.

Here are several steps to add the accuracy of the results.

- For experiment 1, we could adopt wearable devices to track the activity of users instead of asking for user responses.

- For experiment 2, we could set up a real-time timer connected to the projects they are working on. When the participants start to work on the projects, the timer starts counting.

- We could conduct experiments several times to quantify the indices in the exact range, and reduce human error.

Our team in Cornell Tech 2021 Open Studio